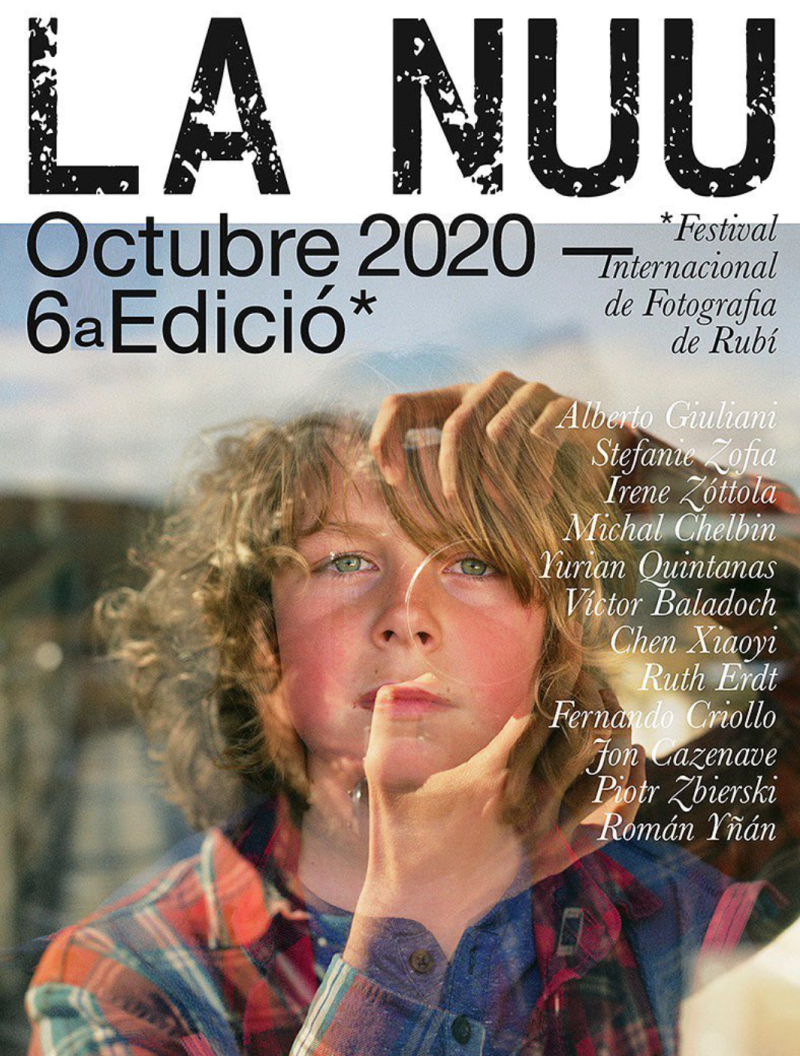

Artists

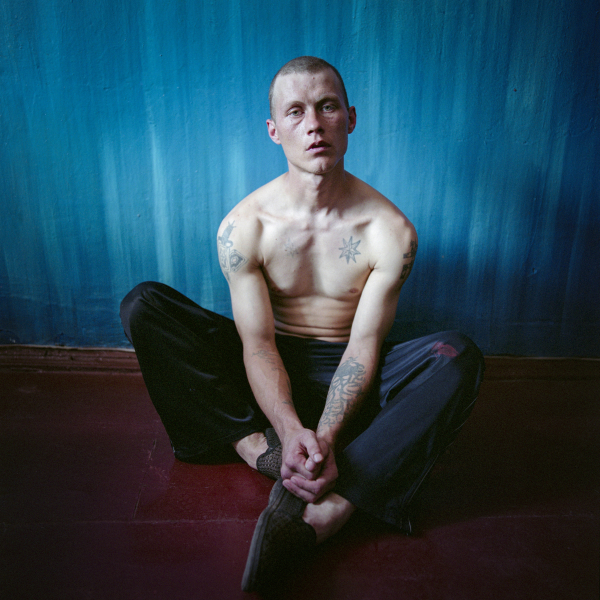

Michal Chelbin

(Haifa, Israel 1974)

The first image human beings see at birth is their mother's face, out of focus. The taste for looking into people's faces continues throughout our lives, and that is why portraiture is such a highly appreciated photographic genre.

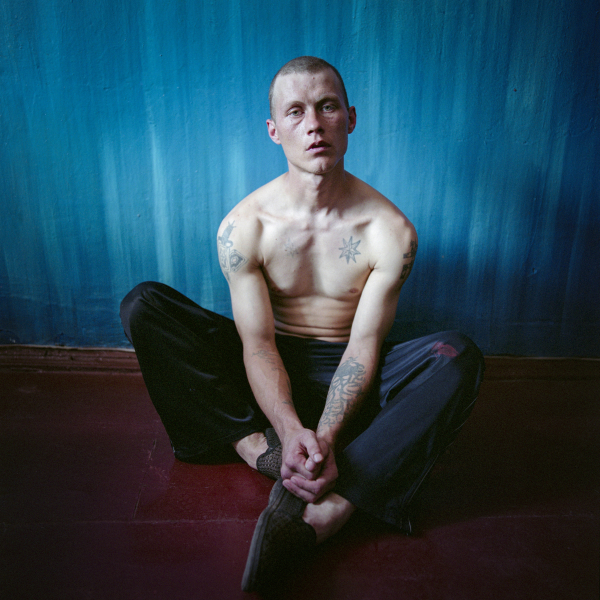

In his photographic practice, Michal Chelbin focuses on classical, square-shaped colour portraits. The face and gaze of his subjects form the centrepiece of his work. In Sailboats and Swans, Michal presents a series of portraits of inmates in various prisons in Ukraine and Russia. The title alludes to the irony of the lovely prints that adorn the walls of these penitentiaries.

In La Nuu we can see his portraits of teenagers barely out of childhood. In prison, these young people are under constant surveillance and have to learn to live with both fear and monotonous routine. When we look at them we do not know whether they are thieves, murderers or rapists. We merely notice their fragility and how hard their lives must be. And we realise that the face is not usually the mirror of the soul.

Yurian Quintanas

(Amsterdam, Netherlands, 1983)

In Dream Moons, Yurian Quintanas presents the kind of pataphysical photography that we had already seen in other projects of his, such as Silent Rooms, in which he imagines the life of his home when he is not there. Pataphysics is, according to its inventor, the surrealist Alfred Jarry, the science of imaginary solutions. In the pataphysical universe, everything is abnormal and extraordinary. The rule that governs it is the exception to the exception. The term pataphysical is a contraction of the Greek epi meta ta physika, and refers to everything that is beyond physics.

In Dream Moons, then, the everyday space becomes the space of a surreal, absurd world. Here we see a sequences of works that combines photographs and texts to take us into a dreamlike world. Small black-and-white still lifes inspired the secret life of objects; waves of water forming infinite concentric circles that illuminate the skin of things; ghost doors; houses that float in the middle of sleep; and so on.

The playful component of existence and, therefore, of the art supported by the Dadaists, is recorded here in order to, in the artist’s own words: “transform all that palpable and evident reality and adapt it to my speech, thus speaking not only about the tangible but also about what we do not see”.

Alberto Giuliani

(Pesaro, Italy, 1975 )

The Catalan writer Josep Pla began his diary The Grey Notebook on March 8, 1918 with the words: “there is so much flu they have had to close the University”.

This year 2020 will be marked indelibly in our personal memories. Unfortunately, it is too soon to know whether the extraordinary event we have witnessed will change our collective history. At present, we all believe it will. But it is never easy to judge the present, nor to describe it in images.

The COVID-19 pandemic and the lockdown imposed in order to combat the virus enabled us to discover our homes as spaces of refuge and seclusion. From our windows, we could see the deserted city streets, and we could also hear the birds.

Alberto Giuliani could have chosen many subjects to make a record of these days: people wearing face masks, queues for basic supplies or patients admitted to the emergency room, but he had the mental agility and visual intelligence to notice one small detail.

The faces of health workers at the Hospital of San Salvatore in Pesaro, after exhausting twelve-hour shifts were marked by the rubbing of their surgical masks and the sweat of fatigue.

The irritated skin of these doctors and nurses are a symbol of the fight against the virus, as well as of the scars that the pandemic will leave on our society.

Accordingly, Alberto Giuliani’s photographic project pays homage to the inestimable work that health workers perform day in, day out.

Román Yñán

(Sant Adrià de Besòs, 1976)

“Hello, my name is Román Yñán and I take photos of my family”. That is how this creative introduces his most personal work, photo diaries in which he records the daily life of his family. The images show different spaces: the interior of the family home – the sofa, the bathroom, the kitchen, the bedrooms; the public space –streets, funfairs, the supermarket; and the natural environment – the woods and the beach when the family is enjoying some leisure time.

As Gaston Bachelard notes in his essay The Poetics of Space: “Any space that the imagination makes possible is a space of intimacy; a space that becomes ours becomes a home, a vessel that holds us, a cosmos of its own”.

Román Yñán captures the “intimate immensity” of the family space in a series of constantly evolving and expanding images, using the flash, natural light, colour and colour stains, and occasionally black and white photography.

Here, the photographic act becomes a family dynamic and a creative game that requires the engagement of all its members. As a result, the family album goes beyond its usual scope to become a space for playful experimentation. A world of its own for all to enjoy.

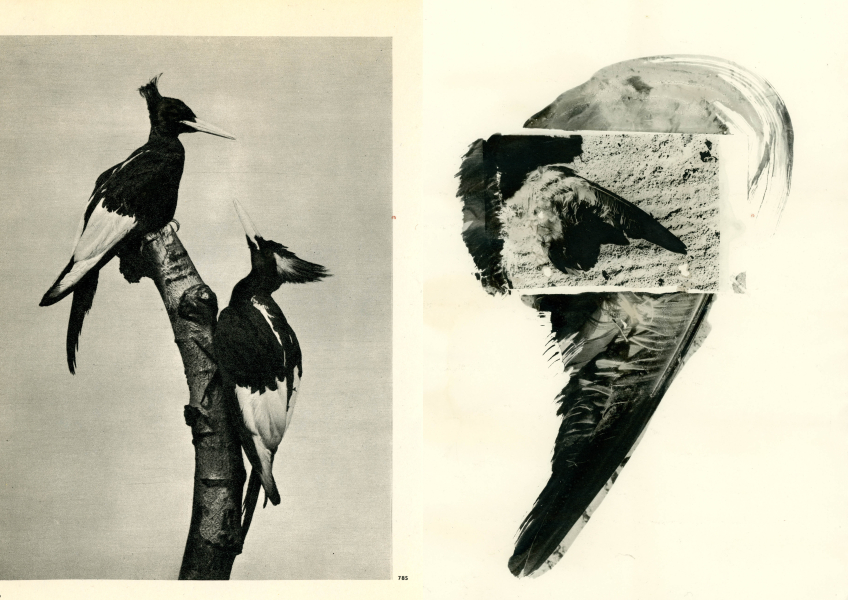

Irene Zóttola

(Madrid, Spain, 1986 )

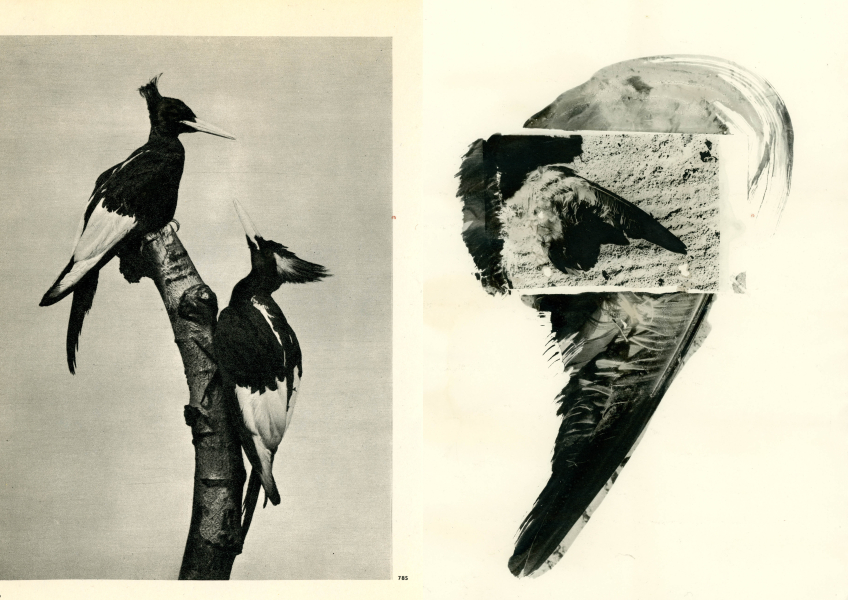

Irene Zóttola’s black-and-white photographs are inscribed with both the written word and painterly traces of liquid emulsion. Hers is a photo-textual practice that also employs other creative strategies, such as image appropriation and intervention. The materiality of analogue photography enables her to use different photosensitive supports to construct a peculiar, dreamlike, poetic world.

In Icarus, she emulsifies the pages of an encyclopaedia of birds to develop superimposed images that operate as concentric circles of meaning. The flight of birds and the myth of Icarus, the desire to fly and the danger of falling, are allegories of human existence and our search for meaning.

As in the Persian poet Attar’s work The Conference of the Birds, we find here a metaphor for the path of life as a spiritual journey. Thirty thousand birds fly off to find Simurgh, the king of the birds. Most will lose their lives during this dangerous odyssey, and just thirty of them will survive, only to discover that the Simurgh lives within each of us. Wings and birds, then, as symbols of the human soul.

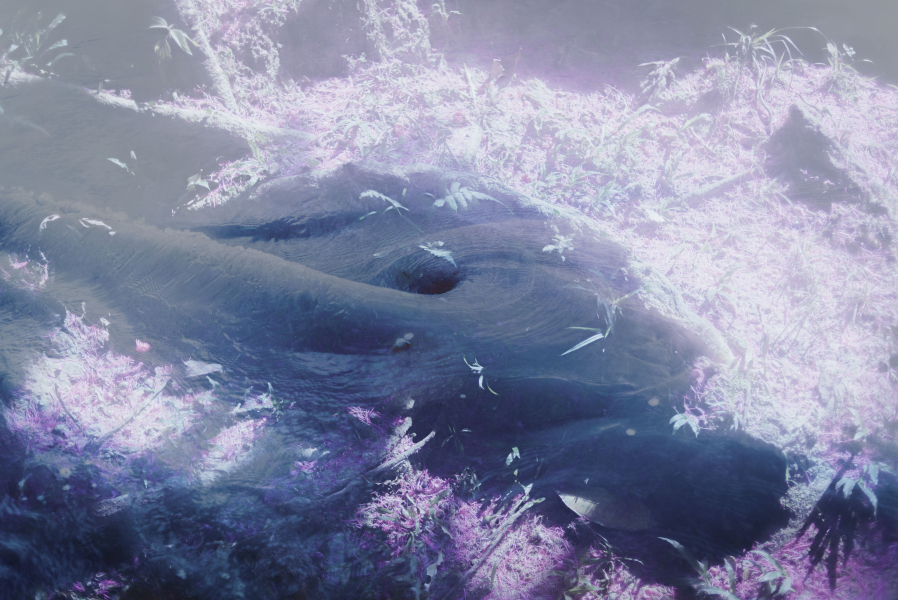

Chen Xiaoyi

(Sichuan, China, 1992 )

“If a tree falls in a forest and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound?”

This famous Zen Buddhist koan suggests a series of questions about our perception and understanding of reality.

Unlike Western philosophy, Eastern philosophies such as Taoism and Zen Buddhism attach more importance to intuition than to logical thinking. Moreover, they reveal just how insufficient language is for ascertaining the ultimate reality of things.

As she herself says, Chen Xiaoyi entitled her series of photographs Koan in an attempt to place herself in a preverbal territory. She uses photography as a tool to get under the surface of things and focus on the most basic forms of existence in the universe. This philosophical approach is aimed at fostering the awakening of a spiritual consciousness.

Her work is formed by images of abstract landscapes like black ink stains on paper. Photographs of mountains and of water (shan shui).

Elements from nature, reduced to their most basic components. Chen Xiaoyi's work emulates the spiritual conception of the Chinese painterly tradition, in which notions of emptiness and fullness structure the composition of the pictorial image.

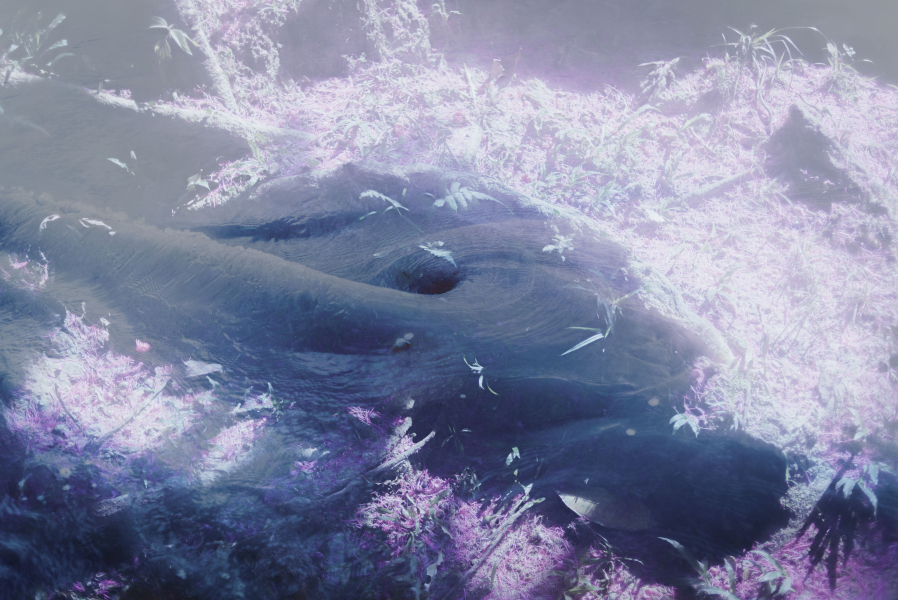

Piotr Zbierski

(Lodz, Poland, 1987)

The musician and poet Patti Smith wrote the following about this Polish photographer in her preface to his previous work: “your fingers press the shutter through the mist / death rests on the silk of an infernal innocence”.

To create Echoes Shades, Piotr Zbierski travelled widely to photograph different communities around the world. Tribes that still maintain primordial links with nature and the cycles of death and rebirth. Animist cultures like the Paradangan in Indonesia, shamanistic traditions in Siberia or the beliefs of people in the Omo region of Ethiopia. Peoples and tribes that continue to perform the rituals and ceremonies of surviving ancestral traditions.

His photographs appear like memories of a present still connected to a past that becomes lost in the mists of time. A meditation on the relationship between culture and nature and how people express the connections between material and spiritual reality.

Zbierski’s visual approach is based on the use of square black-and-wide photos, while he also loves toy cameras and is interested in technical processes that damage the image. The Holga and Polaroid cameras he uses assist him in his search for error and imperfection. Incoming light that burns the negative, clearly noticeable grain, streaks and stains caused during development that add new textures to the photograph. This lack of control and the instability of the images transports the spectator to a purely emotional terrain where the concepts of myth and rite frame Zbierski’s portrayal of a delicate poetic world.

Fernando Criollo

(Lima, Peru 1991)

In ancient Greece, the temenos was a sacred space, a piece of land cut off and consecrated to a god where profane uses were totally forbidden. Before entering, it was necessary to perform a cleansing and purification ritual, as this was a space completely separate from everyday life.

Fernando Criollo’s work Uku Pacha (Ukhu Pacha, “Inner World”) takes us to a sacred space full of violence. In the supernatural world portrayed in these photographs, all the elements of nature – caves, lakes, icy abysses, mountains, stars, fire, lightning and so on – are populated by gods. And in the centre is a crack of light where naked bodies appear like the shadows of a shadow to perform a ritual dance.

Black-and-white photographs full of darkness, photographs whose red colour is like the blood of an animal sacrificed on a stone altar, negative images giving a glimpse into the eye of a hurricane. The primary colours of the beginning of the world.

Convulsive beauty materialised, as Fernando Criollo says, “by symbolic and metaphorical images through which we can enter a new territory transfigured by its own light, inspired by the articulation of impossible geographies and violence, generating a testimony to contemporary spirituality

Victor Baladoch

(Rubí, Spain,1991 )

We all have a body. This is indisputably true. There are those who say that it is the only thing we have and the only thing that we really are. Gaston Bachelard wrote that “the human body is a house and a world. The territory defined by our own extension is the most intimate refuge”. When we approach the body we discover a universe of unfathomable immensity.

Víctor Baladoch, a visual and sound artist from Rubí, uses the space of his body to enact a process of destructive creation. The cosmic links of the life and death cycles of matter related to the fragility of human existence.

His photographs are clearly influenced by the image-action of performative photography, and by the idea of the body as a battlefield as defined by the conceptual artist Barbara Kruger.

The self-portraits Baladoch presents form part of an organic whole. A fragmented body in hand-to-hand combat that both strikes and is struck. A creative journey that fuses videotapes, cassette recordings, sound manipulation and generally scorned media and printing techniques such as photocopying.

Baladoch’s artistic strategies include the appropriation of images and rephotography, even from his computer screen, usually in black-and-white works that are full of noise.

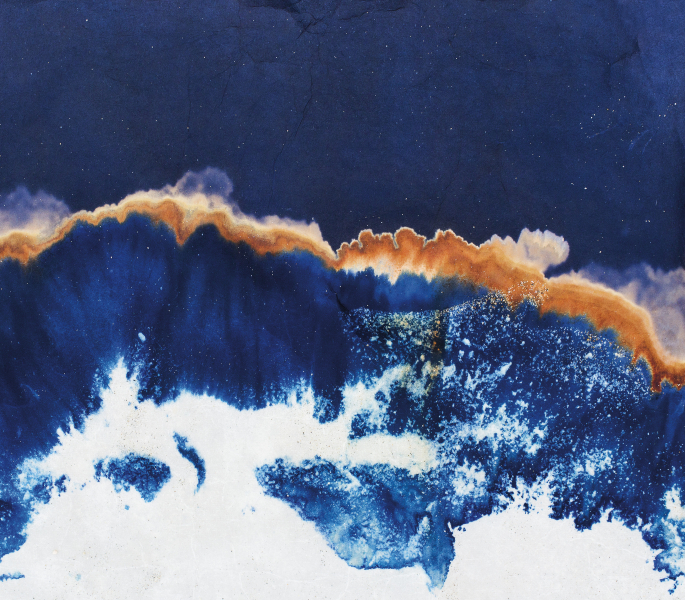

Jon Cazenave

(Donostia-San Sebastián, 1978)

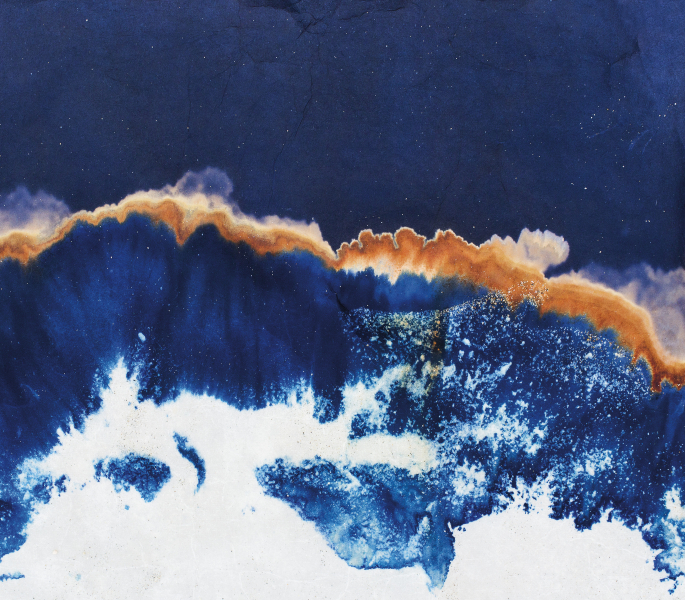

In this image the sea has painted itself. The sound of the waves captured by sunlight. The artist was using the cyanotype technique on washi – a Japanese craft paper – when it accidentally fell into the sea and the salt began to oxidise the chemicals in the emulsion. Blue and ochre tones and the textured white of the paper formed an organic whole. Photographs that reveal ground zero in the photographic act.

Jon Cazenave worked on his project in Takematsu, a village on Shijoku Island in Japan, for two months. The images we can see at La Nuu form part of this work, entitled OMAJI. In his work, Cazenave uses various photographic approaches: vintage techniques, analogue photography, digital photography and screenshots of Google maps of Seto Inland Sea. In short, his practice embodies a compendium of technological changes reflecting the history of photography.

Jon Cazenave's conception of the landscape is paradoxical, as the nature he captures in his images seems to belong to a moment before human existence. A remote time full of silence and without a human gaze to generate landscape. A spiritual journey to the beginning of all things. A path to nature in its purest state.

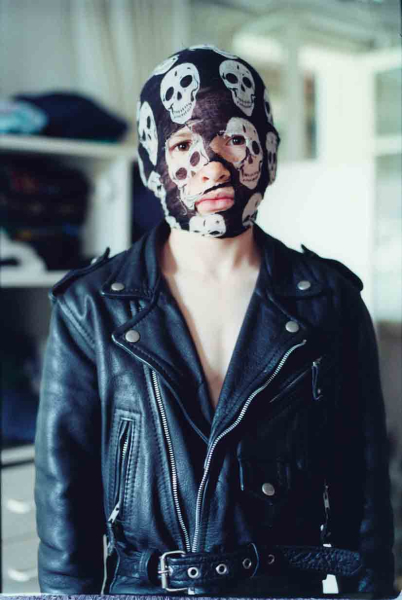

Stefanie Zofia Schulz

(Nagold, Germany, 1987)

In her essay Contra el mapa (“Against the Map”), the art critic Estrella de Diego notes that our usual perception of maps is that they are a reliable graphic representation of a geographical space and that we take their objectivity for granted. We tend to forget, she says, that maps – like any other cultural representation –make a new description of the world “in terms of power and cultural practices, preferences and priorities.”

The scalpel-like border that separates states has led to the creation of immigration laws and legislation that limits the movement of people.

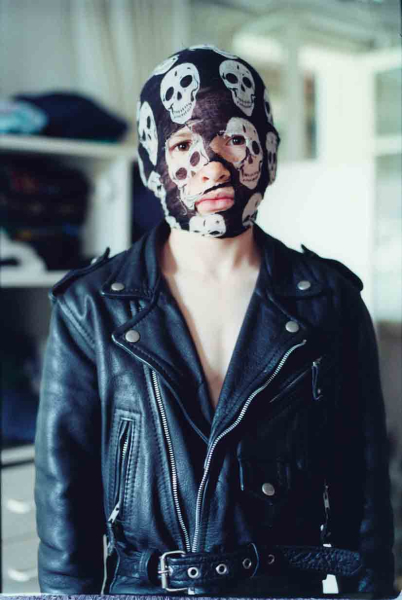

The photographer Stefanie Zofia Schulz was born in a refugee camp for exiles from Poland and Russia in Nagold (Germany). Her work Duldung (“Tolerance”) documents the lives of young people living in Germany's largest housing facility for migrants and refugees from around the world. Located on the outskirts of the small town of Lebach-Jabach, this facility provides initial temporary accommodation before inhabitants are moved to another location. Very often they are forced to wait for years, an eternity.

Monotony accompanies these young people, lost in the bureaucracy of an administration that does not recognise their legal right to be in the country and which makes it impossible for them to get on with their lives. Their faces are hidden or partially veiled as if they were not allowed any kind of identity. Everything reminds them that their presence is tolerated but not welcome.

Duldung forms part of the collective exhibition Off the Margins, organised by Organ Vida and included in the project “From St. Germain to the EU: 100 years a Border”, produced with the support of the Europe for Citizens Programme. Besides Stefanie Zofia Schulz, the show, curated by Barbara Gregov, Luja Simunovic and Lea Vene, also features works by the photographers Verena Blok (Netherlands) and Marvin Bonheur (France).

“From St. Germain to the EU: 100 Years a Border” is a project developed by the Drustvo za evropsko (SI) association, whose members are Organ Vida-International Photography Organization (CRO), Osterreichische Gesellschaft fur Kinderphilosophie (AT) and the Asociación Cultural Ull per Ull (BCN).

The project is cofinanced by Europe for Citizens, a European Union programme.

Ruth Erdt

(Zurich, Switzerland, 1965)

The images that the photographer and artist Ruth Erdt presents in her work The Gang are from an intimate diary about her life or at least what we as spectators assume is her life. The very title of the work, suggesting a criminal group, warns us of the necessary ironic distancing from what would seem to be a collection of photographs of her family and everyday life.

The title refers to a group whose members are primarily linked by violence, so we never know for sure whether this is an album of real or invented memories. We cannot quite understand if it is an homage to the family as a refuge or a protest against it as a suffocating prison.

This tension is generated by Erdt’s portrayal of the family space as a place for fiction in which we sometimes intuit the veiled threat of hidden violence.

Self-portraits and nudes of the artist, photographs of her children, her partner, family and friends, small, eerie objects and, in the midst of everything, unknown models that become part of the visual discourse in this fictional family album.

The photographer eschews all documentary intent even though she still uses the usual codes of the genre in order to subvert the framework of reality and what we believe is normal.

Her images are direct, stubbornly frontal, seeking immediacy. These are both colour and black-and-white photographs into which natural light enters through the window, creating warm or cold tones according to the position of the sun or the photographer’s merciless use of the flash.

Images that examine an emotional landscape from which to proclaim that sharing fiction forms an intimate part of our lives.

Leitmotiv

Body and Stone. Available Spaces

In one of his most famous poems, the poet Salvatore Quasimodo wrote that “Everyone stands alone at the heart of the world”. The short verse ends with the lines “pierced by a ray of sunshine / and suddenly it’s evening.”

The poem reminds us of the inexorable passage of time, but it also speaks to us

of the space where human existence grows. Our private geography, the space where we live.

Under the title Body and Stone. Available Spaces, the sixth La Nuu photography festival presents a series of works by various authors from around the world whose different perspectives all suggest a meditation on the relationships that human beings maintain with their material environment.

Our body both is and occupies a space. According to the philosopher Otto Friedrich Bollnow in his work Human Space, the problem of the spatial structure of human existence carries the same weight as the question of temporality. We live and act in space, and in it both our own personal lives and the collective life of humanity develop.

In our title, we use stone as a metaphor for the material environment, whether natural or artificial, in which we conduct our day-to-day lives. So, stone is both a representative element of nature and a key material in human creations: houses, temples, cities, etc.

Natural space/artificial space. Sacred space/profane space. Anthropological space/nonplace (Marc Augé) and so on. Not to mention socially and politically stratified spaces such as neighbourhoods, borders and all the boundaries that mark the division between inside and outside.

The term topophilia, popularised by the Chinese geographer Yi-Fu Tuan, helps us to weave together the concepts of feeling and place. Topophilia describes the emotional ties between people and the space that surrounds them, defining perceptions of, attitudes towards and values concerning the environment that affect our worldview and vary according to culture and historical period.

Human beings are basically visual animals, but looking and seeing the world is also a cultural act determined by a set of socially structured beliefs. As Yi-Fu Tuan points out, the concepts of culture and environment overlap in the same way as the concepts of humanity and nature.

Mountains are a paradigmatic case of cultural changes in attitude to the environment over time. For the Ancient Greeks, mountains were a wild and hostile space that inspired reverential respect. We should remember that Mount Olympus was the home of the gods, while in Japan Mount Fuji is still considered a sacred mountain by the Shinto religion.

In the West, the aesthetic appreciation of nature is a relatively recent phenomenon. There is a historical anecdote that perfectly explains this circumstance. On April 26, 1336, Petrarch began the ascent of Mount Ventoux and, as he wrote in a letter, he did so not for any practical reason but merely “to see what so great a height had to offer”. To admire and enjoy the landscape, a completely unusual attitude in those days, anticipating the Romantic fervour for contemplating the indomitable splendour of nature. So unusual in those days that, during his climb, Petrarch met a shepherd from the area who tried to persuade him to come to his senses and abandon that mad exploit.

The idea of landscape is a cultural construct that emerged in Europe with the birth of Humanism and the Renaissance. In China, aesthetic appreciation of the landscape dates to an earlier period (around the second century AD), while the landscape painting genre (known as shan shui) also dates back to a much earlier time in the Asian country.

This new aesthetic concept, the landscape, needs someone to look, and an environment to be looked at. The landscape does not belong to nature; it is human beings that generate the landscape with their gaze, pouring their feelings into it. In this way, nature is reconstructed by the gaze of a person who segments part of the whole and individualises it into an autonomous structure.

As Gema Pastor Andrés points out in her essay Como verde y el paisaje inalcanzable. Paradojas del (cuerpo y el) paisaje fotográfico contemporáneo [How Green and the Unattainable Landscape. Paradoxes of (the Body and the) Contemporary Photographic Landscape]:

“It is a personal gaze at that environment, not the environment itself. Humans grasp space through their sense of sight, and generate landscapes by their presence in the environment, through their gaze... The place looked at causes feelings that are reflected in representations”.

Landscape painting in the West was originally based on figurative realism and the application of linear perspective, discovered during the Renaissance period. Later, the nature idealised by Romantic artists in their paintings was internalised by spectators who subsequently projected this new sensibility onto the real landscape.

Since its beginnings, photography has been considered a form of visual representation that is much more faithful to reality than painting, and the new artform soon took centre stage in the tradition of depicting the landscape. The ideal landscapes of travel magazines, nature journals and postcards created an imagery on which we constructed our concept of the beauty of the environment. Photographs of everything worth seeing. It is strange to note that the very icon used to indicate a place of tourist interest is often a camera.

Images are intended as reflections of reality, but reality often becomes a reflection of these images.

The usual perception of a photograph is that it is a reliable and objective mirror reflection of the world, but this is nothing more than a cultural convention like many that govern our lives. Behind an image is always the perspective of someone looking, whether consciously or unconsciously.

The infinite circle of images.

So, our view of the world creates realities that we seek to capture in photographs, and these images then help to shape our view of the world.

Let us now look at the works presented at this, the sixth La Nuu photography festival, and listen to what they say to us.