Artists

Toru Morimoto

(Akashi, Japan, 1972)

Just as in Greek mythology Poseidon controls and unleashes the earthquakes, in Japanese mythology this phenomenon of nature is also under the jurisdiction of the sea. The namazu, a giant catfish that inhabits the depths of the sea, is responsible for the earth shaking. On May 11th 2011, a 9.0 magnitude earthquake wrecked the area of Tohoku, in Japan. Immediately afterwards, a devastating tsunami destroyed all towns along the shoreline and provoked the nuclear accident in Fukushima. More than 15.800 people died in the catastrophe. The horror of shipwrecking on solid ground.

Natnada Marchal

(Paris, France, 1988)

Located in the Eastern end of Siberia, Yakutia is crossed by the “Kolyma” highway. This 2.032 km-long road spreads between the capital of Yakutsk and the harbouring city of Magadan. The place is known for being the coldest inhabited region in the world, where temperatures drop below minus 60 Celsius degrees. A frozen hell where, despite such tough conditions, life is still possible. As in any great trip, both private and external landscapes blend in these frontal snapshots. No matter how far we go, we are always accompanied by ourselves. Our lives do not stop when we travel. As we come back, we are not the same people anymore. Reality is not the same.

Miquel Llonch

(Terrassa, Spain, 1963)

“In the Fields of Gold” is a work about edges and drifting. Landscapes and human figures under a night sky dyed golden by the city lights. A barely starry sky and a space located in the blurry limits of suburbia, a no man’s land that does not belong to the countryside nor to the city. A fragile nature and a timid city conforming an emotional refuge, a place of silence and peace. A gloomy environment that uncovers the beauty of things and the echo our footsteps leave behind.

Muge

(Chogqing, China, 1979)

Every good trip is always a return home. It is not necessary to travel in order to travel. “Go Home” documents the changes the photographer’s homeland has undergone due to the construction of the Three Gorges Dam. These images put together a sort of magic depiction of local customs and manners where both landscape and humanity vanish inside the fog. A dreamlike world where past, present and future are drown in nostalgia. The inhabitants of the area have lost their houses and farmlands under the waters of this huge dam.

Muhammad Fadli

(Jakarta, Indonesia, 1984)

In many Indonesian cities a new community has arisen: young Metalheads, Punks and Rastafarians who are fanatical about Vespa scooters and who customize their bikes with limitless creativity. The so-called “Vespa Warriors” look like riders from the post-Apocalyptic world of the Mad Max movies. They may decorate their Vespas with a buffalo skeleton, a high voltage pole, bamboo and machine guns, and they may build them all the way over with trees and DIY materials. These motorbike riders have escaped the harshness of reality in order to sail their vast country on the back of their beautiful, strange artefacts.

Xiaoxiao Xu

(Qingtian, China, 1984)

“Aeronautics in the Backyard” is a fairy-tale story about the dream of flying. In different places throughout China, farmers are trying to build their own airplanes. They may not be adequately trained nor have the economic resources the enterprise requires, but they draw their plans, they recycle all the scrap metal they can find and they use domestic tools to follow their chimeric dream. Some of these men have spent decades shutting themselves in their backyards, dedicating all their free time to building flying machines that have never left the ground. They have become shipwrecked by their own choice, but these aeronauts have got the guts to follow their dreams and choose a personal path of freedom and creativity.

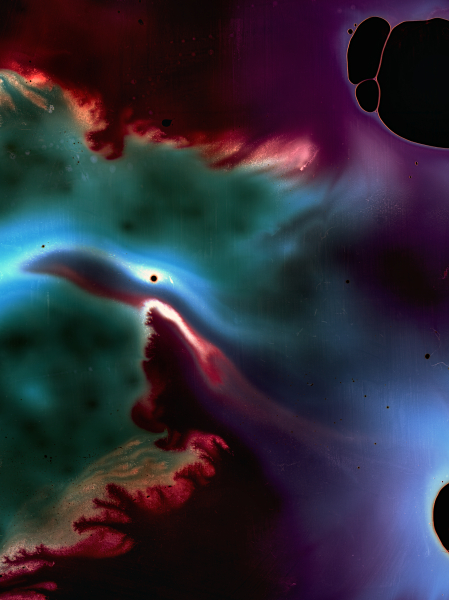

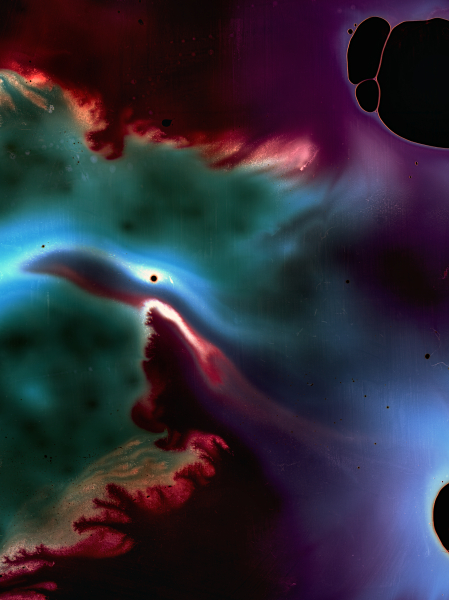

Arnau Blanch

(Barcelona, Spain, 1983)

“Man is a god when he dreams and a beggar when he thinks”, wrote Hölderlin. The intoxicating images of “Twilight Zone” explore the limits between photography and painting, between dream and wakefulness. These are abstract forms and liquid colours that emerge from the primary materiality of the photographic image. Camera-less experimental processes that play with the medium and the chemical substances that photography is made up of. The effect of narcotics as a path towards the knowledge of the self.

Enrique Fraga

(Madrid, Spain, 1975)

We can travel non-stop without going anywhere. Visit all kinds of places without seeing anything at all. We may fall asleep in the bed of a hotel in New York and wake up in a restaurant in Hong Kong. “Platform” speaks of the loneliness of the shipwrecked people who think they are steering the helm of their own lives. High executives and successful businessmen who always travel on Business Class and who wait for their planes at the airport VIP lounge. A lifestyle that is characterized by the pride of belonging in a select group of winners and the hidden sadness of the transit time between two flights.

Marie Sordat

(Tours, France, 1976)

Marie Sordat’s images are both beautiful and fascinating. They picture a trip in darkness that does not dismiss its moments of light. A world full of dangers, but also a magical one. Her black and white strokes are harsh, but there is always a place for sweetness on them. Kids who run, who dream, who look at the camera protected by their parents’ arms. Animals that lazily curl up, sometimes with a sad look, lost and helpless in the street. Human forms and figures that refer us to the primordial fear of loss. The fear of loneliness and absence. Above it all, nevertheless, is the love for life.

Rafael Tanaka Monzó

(Castellón de la Plana, Spain, 1969)

A night made of images. These photographs remain in a constant fight to become something, they are always on the verge of vanishing. They flicker like branches whipped by the wind, lines of black ink over a water surface. They seem to have been made in order to dream our past and remember our future.

Ester Vonplon

(Zurich, Switzerland, 1980)

Giant chunks of ice that get detached and drift away, eternal glaciers, twisted pieces of cloth over astonishing stretches of frozen water. Premonitory landscapes that reveal a frozen horizon for humanity and the earth. In Vonplon’s photographs, the Arctic nature reminds us of the wreckage from a shipwreck. An imposing but also fragile ecosystem that is threatened by global warming. Her images perform the requiem for this vanishing natural world and the solitude of our planet.

Klavdij Sluban

(Paris, France, 1963)

“East to East” describes a trip between Eastern Europe and China, and it collects a work done throughout a long period of time. Photographs of deep blackness and slow exposure that make the image shake. Cold landscapes cut open by the Trans-Siberian Railway. Erri de Luca wrote about the work of Klavdij Sluban: “The photographer was nostalgic for the snow of his childhood, which surrounded him in his corner of the world, but here the snow has become a white cancer: it doesn’t cover the ground, but consumes it. The silence is oppressive”.

Leitmotiv

Shipwrecks

We all are shipwrecked. We try to stay afloat by our own strength, or holding to any life raft available. The Italian poet Leopardi wrote: “And to shipwreck is sweet to me in this sea”. Seneca, the philosopher from Córdoba, confessed: “Before becoming a sailor, I was shipwrecked”.

Philosophy and literature have taken the metaphor of sailing and shipwrecking as paradigms for the fate of human existence. Leaving solid ground and letting go of the security of a harbour implies sailing the instability of the open sea. Setting forth any maritime journey entails accepting the possibility of becoming shipwrecked. In his book Shipwreck With Spectator, from the reading of a passage from Lucretius’s De rerum natura, Hans Blumenberg analyses the varied repertoire of the shipwrecking metaphor and the symbolic relationship between life and sea travel. And he does so in order to look into the success and failure of human enterprises, and the role of the uninvolved spectator, safe from other people’s misfortunes.

The different photographic works submitted to this edition of the La Nuu festival allow us both to reflect on the cultural image of the shipwreck and to show the continuous bond between philosophical thought, literary creation and visual representation.

Humanity has always felt the need to widen the bounds of its everyday reality, both physical and mental, and has set sail driven by its desire of knowledge or the search for a better life.

Ever since the Classical world, the idea of travel has acted upon the collective conscience as an ambivalent metaphor. On the one hand, it stands as a path full of dangers one should avoid and, on the other, as the road that leads to wisdom.

Sailors of old had the motto: “Living isn’t necessary, sailing is”.

In Ethics for Shipwrecked People, José Antonio Marina writes: “Sailing is the victory of the will over determinism”.

Surviving a shipwreck may also become a starting point for life, as one leaves all the burdens of the past behind to start all over. Or, as Samuel Beckett would put it, as one fails again in order to fail better.

In Romantic times, painting showed great interest in capturing the power of Nature, especially through the depiction of rough seas. Shipwrecks became a recurring pictorial motif. The tempest, nature out of control, was used to confront us with his our existential uncertainty. Troubled waters attested to inner troubles.

The Romantic trip was always a private search for the self and became an aesthetic ideal that has lived on until now.

In her study Shipwrecks, the art historian Esperanza Guillén reminds us that “due to its dynamic condition, travelling relates to the spiritual longing, to the wish and anxiety for changing our circumstances. Thus, shipwrecking implies a tragic end for our existential journey and for those human hopes”.

According to Classical mythology and Biblical texts, the sea is a natural limit set by divine wisdom, and solid ground is the most suitable dwelling place for the human kind.

The violation of this division is as much of a sacrilege as the one Prometheus committed when he stole the fire from the gods. Both air navigation (the myth of Daedalus and Icarus) and sea navigation belong in the same context. Human pride insists on binding that which the divine order separated beyond human reach.

The shipwreck topic is so wide that its metaphoric reach has spread out into many different fields of the human experience, both individually and collectively.